|

Slugs and snails have a true champion in Imogen Cavadino, an entomologist who is carrying out research for the RHS. We were treated to a wealth of information with up-close-and-personal photography of these oft-maligned creatures. Slugs evolved from snails as they simplified their coiled shells and diverged into different families. There’s even such a thing as a semi-slug, one that can’t retract into the shell it carries on top. Some slug species still have a visible pale mantle under the surface, marking their vestigial shell which serves as storage for calcium salts. The majority of snails have shells which coil to the right, developing asymmetrically via torsion, so that both their respiratory pore and anus end up on the right side of their heads. They are so dependent on moisture that if deprived, they can create an epiphragm to seal themselves in and succumb to a dormant state. Quick to revive if the conditions improve, Imogen told us that a snail was once stuck on a postcard as an exhibit in the British Museum (before they knew about their dormancy behaviour) and stunned everyone by making an escape. For a researcher, the slime colour can be useful for identifying the species. Slugs produce two types of mucus for defence and movement. We heard that the netted field slug (deroceras reticulatum - above on the left) is the most harmful to our agricultural activities, making a feast of root vegetables in the autumn, but the cellar slugs (Limacus sp. - on the right) feed on rotting material, fungi, lichens and algae and are therefore blameless.

The Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) has been campaigning, with Imogen heavily involved with their media activity, to dispel the myths that all slugs are enemies of the gardener. The last big slug survey was done in the 1940s and the RHS’ recent research has been aided by a formal survey conducted by 60 chosen participants around the country, who performed scheduled slug counts, with the glorious total of 21,000 slugs collected and identified in one year. They discovered that non-native species were becoming more dominant, no doubt hitching rides on plants from other countries. New varieties are also being discovered, like the ghost slug (Selenochlamys ysbryda - above centre) with no eyes, first identified in Wales in 2014. Finally, that all important question – how do you euthanise a slug? Obviously, only the types which are eating your veg – please identify them first! The most ethical way is to put them in a sealed container and place in the freezer. Or if you are wanting to maintain their colours for identification purposes, you can drown them in carbonated spring water. On a more positive note, the RHS welcomes recordings from anyone who wants to get involved. You will find information from Imogen on our Wildlife Recording page, about helping to record slug and snail activity. Important: we shall not be at the Victoria Hall in Tisbury for this month's talk on Thurs 17th March due to Covid precautions and the talk will only be available via Zoom. Members, please refer to your emails with the details of the link.

Our speaker Imogen Cavadino has tested positive, yet has kindly confirmed that she is well enough to deliver her talk via Zoom. Due to the rise in cases locally we feel that it's wise for us all not to gather. If you still want to join as a guest for this talk (£2 per ticket for guests) please use the contact form and we shall send out the link to you. We are delighted to share the news that Peter Shallcross was announced as the winner of the Conservation Project of the Year at the Wiltshire Life Awards 2022 ceremony last Friday for his Disease Resistant Elm Project. Well done, Peter!

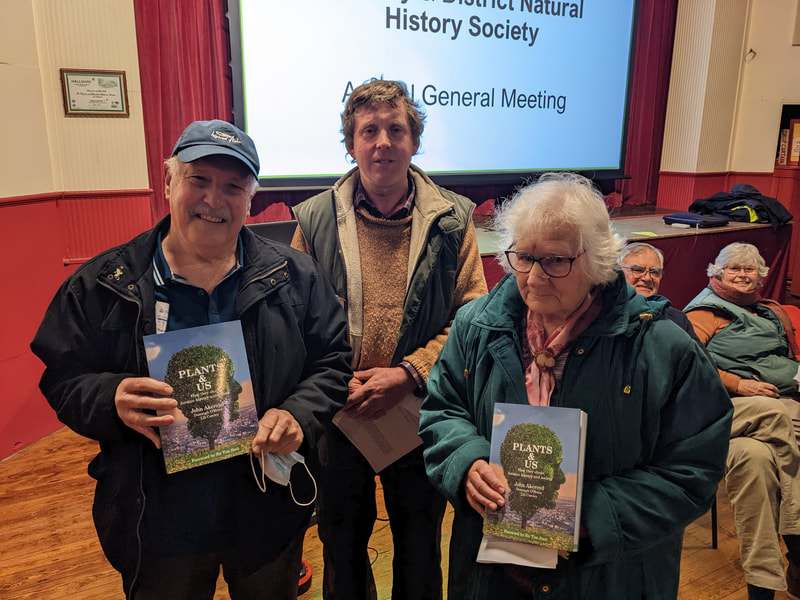

As a token of our gratitude to past committee members, Peter Shallcross presented ‘Plants and Us’ by John Akeroyd to Pete Thompson and Pam Chave at the AGM on 17th February and to Val Hopkinson afterwards, as they were on the very first committee 40 years ago.

Elizabeth Forbes was also presented with an 'Earth from the Air' book by the photographer Yann Arthus-Bertrand, for her work with the Swift project. At 7:30 pm this coming Thursday in the Victoria Hall, Imogen Cavadino is coming to share her knowledge about slugs and snails.

Imogen is an entomologist currently carrying out research funded by the Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) to help in identifying their species, and to discover which ones are responsible for damaging plants, whether in gardens, on farmland or in the wild. She aims to inform pest management strategies so that only those slugs and snails that are actually damaging plants are targeted, reducing control costs as well as potential harm to other wildlife. We've made a few changes to the leaders of the field trips and so there's now an updated file loaded for the programme on the website. Letting you know just in case you've already printed yours out for the year!

The full programme has been uploaded to our Talks and Field Trips pages and can also be found here. We're looking forward to getting out on our first field trip with Peter Shallcross on his early evening river walk on 28th April, but don't forget that we have two more talks still to come on 17th March and 21st April. More information will be coming via email in due course.

In early March, lapwings return to their favoured place to breed. I can still remember them being such a common bird that their evocative courtship call and swooping flight was well known. Now, their population has declined so much that locally only a few pairs come back to just one field. During the 80's, their ancestors nested in the spring barley sown in 'Three Corner Piece,' a stony small field. But then the fence was pulled down, the field enlarged and wheat was planted so the birds moved on. They were then looked after by the Carter family at Place farm, who would search the maize fields before cultivating around them or who would move the nests to safety. When the Carters left, the lapwings left too, as the fields quickly became unsuitable for nesting. Luckily, at that time an environmental scheme came in, which paid for a ‘Lapwing plot' to be prepared for them annually. At least, they had somewhere permanent safe to breed in the middle of an arable field. Sometimes they would nest off the plot and it would take both myself and Geoff Lambert to find them and put down a marker. But even so, the numbers of pairs were still declining year on year, so I gave them a pond for water and a source of insects. I even cut down some hedgerow trees where crows would perch to predate on the chicks.

As lapwings are long lived (up to twenty years) and the old birds faithfully return each year, a lack of breeding success can go unnoticed for years, until finally, the old birds die and no more birds ever return. This year, Nick Adams (a local ecologist with a long RSPB experience) has recommended fencing an area of grass to be grazed by a couple of sheep, which will provide the lapwing chicks with insects. Let's hope that works! All this shows how farming and the countryside has changed even in my working lifetime, and a species which had adapted to a centuries-old agricultural system, suddenly find themselves relics in a hostile environment. If you want to see and hear lapwings, a good place to go is Winterbourne Downs RSPB Nature Reserve near Newton Tony. The whole farm has been converted to suit the habitat requirements of stone curlews (another endangered bird species), and lapwings just happen to like it too. by Andrew Graham |

Photo: Avocets (Izzy Fry)

The headers display photos taken by our members. Do get in touch via the Contact Form if you'd like to submit a photo for selection.

Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed